By Joan Doggrell

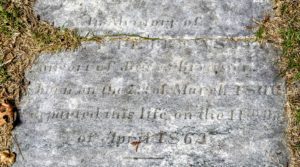

Behind St. Paul’s Memorial Garden wall is a small family cemetery. You won’t see it unless you walk around in back of the wall. This little burying ground once belonged to the Brewster family. It was located in the southwest corner of their dairy farm, which extended all the way from Roscoe Road to Highway 29. The family patriarch, James Brewster, was born in 1799 and died in 1893 at the age of ninety-four. Janett Brewster was born in 1806 and died 1862. Janett bore James thirteen children.*1

After James Brewster’s death, the surviving Brewster children – there were ten of them — sold their shares of the farm to one of their brothers, P.H. Brewster. He in turn sold it to his brother Angus who conveyed it to his son Jim Brewster. Upon Jim’s death, his son and widow transferred a large section of the property to what is now Forest Lawn Park, the perpetual care cemetery across Roscoe Road from St. Paul’s. Throughout these changes in ownership, the family plot was maintained.

Two acres of the Forest Lawn Park property were transferred to St. Paul’s in the 1960s. Because of the family cemetery, the law insisted that an attempt be made to contact the Brewster descendants. In the church files is a spreadsheet that records the attempts of Attorney Charles Latolla to do just that. In a letter to Lawyers Title Insurance Corporation in Atlanta, Latolla describes the research he has done and asks that it serve legally. The judge in the case eventually decided he had made enough of an effort to find the family and allowed the transfer to take place.

A stipulation in the transfer agreement is that the church restore the Brewster family plot, enclose it in a wrought iron fence, and maintain it for as long as the church continues to exist. In the event the land should cease to be used for church purposes, it will revert to and become a part of Forest Lawn Park.

St. Paul’s, as represented by the vestry, agreed to restore the cemetery and maintain it.

Bill Tudor’s research on the Brewster family revealed some interesting facts about the Brewsters.

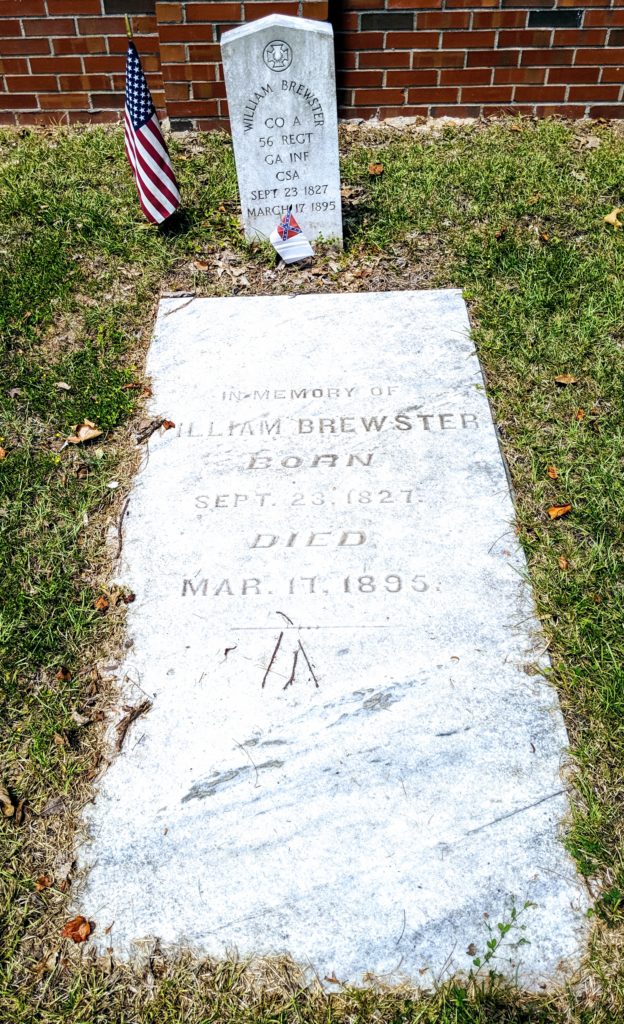

“I have a book on the First Georgia Infantry,” said Bill. “In it there is a list of soldiers who served in that unit which was formed after secession, certainly after the war had started. In the Newnan Guards were four Brewsters: Blake Dempsey, Daniel Ferguson, James Pendleton, and William Brewster. Two of those four are buried at St. Paul’s, William and Daniel.*2

Another son is buried in the Oakland Cemetery. There is no indication of where the fourth of the Civil War soldiers is buried.

There are eight graves in the cemetery: those of James, Janett, and their sons William and Daniel; Lucy Ellen Brewster, daughter of James and Janett who died at age three; Sophia Emma Brewster, another daughter who lived to be nineteen; and Mary Caledonia Camp, daughter of Margaret and A. Camp. Mary Caledonia was two years old and a granddaughter of James and Janett. Seven of the graves lie under engraved marble slabs.

There is also a nameless infant whose grave is covered with bricks. And therein lies a tale.

“When Linda and I first started going to St. Paul’s,” said Bill, “the family cemetery had been neglected for a long time. There were probably seven to nine inches of leaves covering the whole area. As I was mulching out those leaves, I hit something metal. I thought the world was coming to an end. As I brushed away the leaves to find out what I had hit, I saw a small metal grave marker. It said, ‘Unknown Child.’ My mower had damaged it.

“I took the marker to McKoon’s Funeral Home and Crematory, explained the situation to John Davidson there and asked him if there was any way he could make another one. I said I would pay him for it. He came back a few minutes later with one just like it and would not take a cent for it. So I immediately replaced the marker.”

The original had been put there when “Matilda” was reinterred in the Brewster family plot. That was the metal sign that I hit. She was found around 200-250 feet from this cemetery, which raises a lot of questions. Why wasn’t she buried with the rest of the Brewsters? Nobody that I know of has an answer or a good explanation.”

Were you ever at St. Paul’s when the lights blinked for no reason or the elevator moved though no one had pushed the button? Maybe you heard someone say with a nervous goggle, “That must be Matilda.”

Well, who is “Matilda?” Truthfully, no one knows. The name was made up. Her remains were unearthed on church property back in the early 1980s.

Some people, alone in the library or the loft above the parish hall, have sensed her presence. For example, Bill Tudor gives the following account:

“Seven or eight years ago, I was up in the old choir loft, which is in a straight line, probably 20 feet from where Matilda was found. I was working alone – nobody else was in the church that day. The lights would flicker off, and a few seconds later they would come back on. Then they would go back off. I am not a great believer in spirits, but willing to give them the benefit of the doubt. I just said, ‘Honey, I’ll just be here about three or four more minutes, and then I’m about to wrap up. Be patient with me – I’d appreciate it.’ The lights came on and stayed on. I turned them off on my way out.”

There are other folks who have seen strange things. One of our former priests, Father Matthew Greathouse, firmly believed in some type of supernatural being. He claimed to have seen her.

Is an unquiet spirit haunting St. Paul’s? Or is Matilda a figment of overactive imaginations? We don’t know. But there must be a story behind the pathetic little casket that contained her tiny bones.

Lee Daniel was on the Vestry back in the early ‘eighties when what is now the parish hall was being built. The building was going to be the new St. Paul’s church. (At the time, the church was housed in what today is the children’s wing.)

“There was a problem with the design,” said Lee. “The appliances for heating and cooling were to be installed above the nave, in the apex of it.” But parishioners realized they would make too much noise during the service, so it was decided that the units should reside on the outside of the building. While digging a pit for the HVAC, workers came upon the casket of a small child. According to Lee, the backhoe operator hasn’t been seen in Coweta County since. “Apparently the experience shook him up so that he chose to move to other parts of the country!” said Lee.

The cast iron casket was small, about two by three feet. It had been damaged by the back hoe. When Lee and the others opened it, they found bones and bits of clothing.

Why was the casket made of cast iron? Frankie Hardin has a possible explanation. She met the coroner from Fulton County while attending a seminar for aspiring mystery writers. She took the occasion to tell him about Matilda and asked about the cast iron casket. He said that people in the Victorian period (1837-1901) began using iron caskets to prevent the spread of infectious disease, such as smallpox.

Incidentally, smallpox has a long shelf life. If the theory holds true in Matilda’s case, then the persons who opened the casket may have been at risk. Fortunately, there is no record of any of the participants becoming ill.

As a member of the Vestry, Lee was called upon to take charge of this discovery. “The first thing I thought to do,” said Lee, “was to call the coroner.” The coroners arrived, looked the situation over, and said, “I don’t know what to do.”

His suggestion was to call Probate Judge McCoy, who didn’t know what to do either. McCoy said to call Terry Davidson of McKoon’s Funeral Home and Crematory. The McKoon’s personnel knew whom to notify and submitted the necessary paperwork. Davidson’s advice? “Dig another hole, put it all in there, and mark the spot.”

“So Davidson picked a place,” continued Lee. “If you stand in today’s parish hall facing the kitchen and look to your right beneath the second stained glass window, you will pinpoint the spot where we dug a hole and put the remains. We marked the new grave with four cinder blocks: at the head, foot, and both sides.”

When the growing parish got ready to build a third building (the present-day St. Paul’s), someone told the current priest Russell Kendrick (now Bishop of Central Gulf Coast) there was a grave by the sidewalk that ran down to the basement door.

“I know right where the grave is,” said Lee. “Cinder blocks are around it.”

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/ Gang aft agley. Robert Burns.

Someone had moved the blocks.

“However, we dug in the general vicinity and found her again,” said Lee. “Russell said she should be buried in the Brewster cemetery, which is just outside the wall of our Memory Garden, so that is where she is today. We didn’t have a name, so we hung ‘Matilda’ on her. And we still don’t know who she is.”

The only reason to think that Matilda may have had a relation to the Brewster family is the fact that she is buried on Brewster land, close to the family plot. Was she a Brewster? Or the child of a slave?

Could that iron casket have preceded the establishment of the Brewster cemetery? Could “Matilda” have been buried before they set up the family plot? Was a contagious illness the cause of her death and hasty burial outside of the family plot?

An occupant of the Brewster cemetery may know her real name and the story of her brief life. But unless someone finds a letter or diary with a communication from beyond the grave, we will never know.

Notes:

*1 “Interestingly, her tombstone reads, ‘Janett Brewster, Consort of James Brewster,” said Bill. “Where did the word consort come in? I did a little research on the word – there are different variations and definitions – a very close friend, companion. It also seems that in that period of history, if a young couple split up early in life and later one of them found someone else to marry, he or she had no way of contacting the first spouse. So it appears that the ‘consort’ was a wife for all intents and purposes: not legally, but accepted by society because there was no way to find that earlier spouse. That might be the case here.”

*2 Daniel is younger than William, yet Daniel became the sergeant-major of Company A while his older brother was still a private.