What do You Know About St. Paul’s Outreach?

By Joan Doggrell

Before talking to Crystal McCollough, I knew very little about St. Paul’s Outreach program. I knew that Outreach was responsible for disbursing funds to deserving recipients. But I thought the Outreach committee was a single entity headed by a Chair and the usual officers. How wrong I was. That may have been its previous structure, but not anymore.

And why was I talking to Crystal? Because she is Chair for the Community Grants Ministry. More about that shortly. But first, a bit about Crystal. She runs a small business from home, Beautycounter, “a clean beauty brand for men, women, & children.” She is married to Micah McCollough, and they have five children: Ariel, thirteen; Micah Jr, eleven; Eli, nine; Aaron, seven; and Samuel, two.

“And Joey (the Golden Doodle puppy) makes six!” said Crystal. “It’s like having toddler twins when Sammy and Joey are in the house together. One’s running this way, the other’s running that way… It would be easier if they were one species – they would both either sit and color or they’d both play Fetch!”

It’s easy to see she has her hands full. Nevertheless, “I’ve always enjoyed being a servant,” she said. “Father Allan pulled me out of the pew with my newborn Aaron and told me I needed to join the Committee. And I’ve been here ever since.”

Today, Outreach consists of four permanent ministries: Community Grants, The Work of our Hands. Stories of Grace, and Monthly Mission Market. As Christmas approaches, a fifth ministry, Angel Tree, goes to work.

And who is in charge of all these ministries? Why, our own Hazel, of course.

The Community Grants ministry is “tasked with receiving grant applications and voting on whether or not to grant those funds,” said Crystal.

According to St. Paul’s website:

“St. Paul’s makes grants to nonprofit programs that provide basic needs to the most vulnerable of our neighbors. In addition to small grants (typically $2,500 or less), the Community Grants Ministry provides funds to organizations with local or regional affiliation, especially organizations with an Episcopal affiliation, organizations founded by St. Paul’s Episcopal Church or organizations impacted by significant parishioner participation.”

This ministry has been busy this year. Here are the organizations who have received grants to date.

CORRAL, $2,500, to the equine therapy folks. According to their website, “We collaborate with local, referral community partners who identify our at-risk girls and then we pair them with rescued horses.” Check out their website at https://corralriding.org/. They have inspiring stories to tell.

I-58 Mission. “This organization is in Senoia,” said Crystal. “We gave them a grant of $7500. They are like One Roof and Bridging the Gap, only on the other side of the Interstate. That’s a whole community that is part of Coweta County, that we have never touched. They were new the first time we heard about them. We have kept an eye on them, and they’ve grown exponentially. They are doing some wonderful things in their community. We’re really excited to help them out this year.” https://thei58mission.org/

Kairos, $750, the St. Paul’s prison ministry led by Bill Harrison. The Kairos website says, “By sharing the love and forgiveness of Jesus Christ, Kairos hopes to change hearts, transform lives and impact the world.” http://www.kairosprisonministry.org

“…I was in prison, and you came to visit me.” (Matthew 25:36)

Coweta Samaritan Clinic, $2,500. Our own Lou Graner played a major role in getting this health care facility started and served as its Executive Director for almost eight years. The clinic serves uninsured Coweta County residents with limited incomes. https://www.cowetasamaritanclinic.org/

One Roof. “We have a special relationship with them,” said Crystal. “St. Paul’s started the Food Pantry right here in our building. So we have always had a vested interest in One Roof’s success. We do a quarterly grant to them of $2000.” https://oneroofoutreach.org/

“One Roof recently opened a new facility they call The Lodge. When asked to help with that project, we said we would see how we could get other congregations involved to help sustain this. Luckily, they got a large amount of support from some of the downtown churches, so now they are open. We helped support them with a grant of $6,000.”

“The Lodge will house two families at a time for thirty days – women and children coming from homeless situations. The Lodge is a sub-program under the One Roof umbrella, headed by Frankie Hardin. One Roof covers the food pantry, the thrift store, and now The Lodge.”

“So that is how we dispersed our money for this year,” added Crystal. “We still have a good bit yet. We are waiting to see what Angel Tree comes out at. And we may have more grant applications.”

The Work of our Hands ministry, chaired by Joshua Wieda, identifies ways parishioners can go beyond writing a check. The ministry encourages hands-on participation.

According to Crystal, St. Paul’s participated in Bridging the Gap earlier this year, and Backpack Buddies is happening in October. A couple days of the week, Bridging the Gap provides a hot meal and food distribution. St. Paul’s volunteers provided a hot breakfast on March 9 of this year, during Lent.

“We had over thirty show up to help serve breakfast, with casseroles in hand, some gluten free – we were very conscious of that. There was also a set of volunteers in the warehouse who were dispersing the food. But we were there to give that touch, Hazel was on hand to give a sermon, and the Children’s Choir was there. I was really pleased to see that turnout,” said Crystal.

Their next project will be Backpack Buddies. “This is an organization that sends underprivileged children home with easy-to-heat and eat food,” said Crystal. “We have a large population of children who are on free or reduced-cost lunch. Backpack Buddies discreetly packs bags with canned ravioli, Ramen noodles, peanut butter crackers, anything children and their families can easily heat so they can have a nice meal over the weekend. The only place these children get a hot meal is at school.”

The school identifies the children who need food, typically from the list of those getting free or reduced-cost lunches or whom teachers recognize because they’re hungry.

I had to ask: “Don’t their families get welfare and Food Stamps? Why are so many children hungry?”

Crystal did not attempt to explain. Wisely, she simply helps to supply an obvious need. “It’s just the way things are,” she said. “A lot of hungry children are in Coweta County, and the only way they eat is when they are at school. So Backpack Buddies exists to meet that need. This ministry also provides food over school breaks. For example, for Thanksgiving break, they get a larger bag of food. Parents are encouraged to come to the school to pick up these bags.”

St. Paul’s volunteers will be packing bags on Tuesday evening, October 15. On Thursday and Friday, volunteers will take them to the schools for distribution.

“I toted bags for awhile,” said Crystal. “But then when I had Samuel, I couldn’t carry the bags and him too!”

“Arranging for people to come out for those bags is really big,” said Crystal. “Backpack Buddies gets a lot of donations. People just go to BJs and get big pallets of ravioli, chili, and things of that nature to be able to send the babies home with something.”

“I really love Backpack Buddies,” she adds. “The woman who started it has this big, beautiful heart – she’s the owner of the Senoia Coffee Shop. She just saw a need, and went for it, and by the Grace of God, she has had people constantly donating food and money and a constant stream of volunteers to pack up these bags.”

The Monthly Mission Market ministry (MMM) offers opportunities for all parishioners to “assist local nonprofit programs with in-kind gifts by bringing in needed items and placing them in MMM’s shopping cart.”

“We decided on our Monthly Mission Market activities at our first meeting of the year,” said Crystal.

These are the organizations St. Paul’s MMM currently supports with parishioner-donated supplies:

- The Coweta County Food Pantry. Several times throughout the year we request parishioner donations. “I think with the surplus of food we have in this country there is no reason for people to be hungry,” said Crystal.

- Meals on Wheels. Foods such as fruit cups and juices are requested.

- Animal shelter supplies.

- Drive for Backpack Buddies. None was conducted this year.

- The Boys and Girls Club. This year, after-school supplies were donated to Ruth Hill.

- Ansley House. According to their website, it’s “a school for children of families who have experienced homelessness in Atlanta.” “It’s a safe place for them to go and get some education,” explained Crystal. “It’s part of the Episcopal church – St. Luke’s donates the space. Hazel and Jane Murdock learned about it at Diocesan Convention. The school doesn’t have a lot of space to store collections, so we ended up giving them a $500 donation.”

- The I-58 mission or One Roof in December “depending on who has the greatest need for cold weather gear,” said Crystal. “We were able to split those donations last year so both would have coats to hand out, for free, to those who needed them.”

- School Necessities in January, which is “geared more towards teachers because by that time of year they’ve run out of their tissues, hand sanitizer, etc. The plan is to be able to replenish those supplies.”

The Stories of Grace ministry, chaired by Mark Bulford, is tasked with telling “the stories of how St. Paul’s is serving Jesus in our community and will broadcast the stories as appropriate via news media, social media, the blog, and The Lamp.”

According to Crystal, “This ministry is supposed to be a way of sharing what Outreach is up to. But we’re having trouble with that.”

Anyone want to volunteer to make sure such information gets in The Lamp, on St. Paul’s website, and in the Blog? Just raise your hand.

The Angel Tree ministry, chaired by Carrie Wendelburg, functions seasonally. During Advent, the Angel Tree is placed in the Narthex and covered in tags describing Christmas list items for needy individuals and families. Parishioners are invited to take a tag and return the unwrapped item to the collection basket in the Parish Hall. The Angel Tree team uses the items to create a display of generosity in the Parish Hall until the items are distributed.

“Names of deserving persons – those who would have a barren Christmas otherwise – come from DFCS,” explained Crystal. “Then it’s a matter of making sure each child and needy adult has a slip, then sorting through and making sure nothing was left off.”

“Last year we did pick up several bicycles,” added Crystal. “We weren’t given as many bikes as were requested, so we picked some up with Outreach funds. We signed up to provide these gifts, so we need to take care to do so.”

“Carrie Wendelburg is getting ready to start the Angel Tree project this year, so she will need volunteers to help with that. It’s a lot of work, and Alise, her daughter, is off to college now, so Carrie will need some extra hands. Hopefully she will be asking for committee members soon to get Angel Tree up and running.”

Outreach Needs Help!

Crystal’s concluding remarks:

“Volunteering to serve in each of these outreach ministries gives meaning to why we do what we do outside the walls of our church. Now that our committee is split into subcommittees, we don’t have as much participation as we did previously. We are looking for new members. We would like more people for Work of Our Hands and Stories of Grace. Stories of Grace is supposed to be a committee to highlight the goings-on at Outreach as well as let the Church know about other volunteer and service opportunities that they don’t necessarily need to do through the Church.

“Last year we did the agricultural initiative in Haiti. We talked about it a bit, but I feel there was so much more we could have done. I think people would want to know that in Haiti we helped plant a crop of trees so recipients could be sustainable farmers and grow and sell their own crops and make a better life for their families. We have a relationship with these families, but we don’t talk about it.”

The following write-up appeared a newsletter from Bethlehem Ministries, the organization working with Father Bruno in Haiti.

One of the lucky families high in the mountains got help from some Bethlehem Ministry families to plant trees and crops on their steep land.

A year and a half ago some families at St. Paul’s Episcopal in Newnan, Georgia and at First Presbyterian in Athens changed the life trajectory of some Haitian families by giving them the resources to plant their steep land with agro-forests. With that jump start, those families scored. Tree and crop cover are up, erosion is down, and optimism for their kids’ future is growing, all of which has given us the confidence to expand the idea to other communities – four of them in fact. The goals remain the same – help the land produce more, protect it for the future, and build household income using new cropping techniques and equipment to make value-added commodities. Juice from guava fruit, roof rafters from eucalyptus trees, bread from manioc roots, soap from Jatrofa seeds – there are so many plant-based possibilities because Haiti is in the tropics. When farm communities can tap those possibilities, their economy improves. Bethlehem Ministry is helping them do that. Thank you all. JP’s new project, called Land and Livelihood Transformation on Steep Land, is a three-year project focused on 500 participants and beneficiaries with economic benefits reaching many more. It is ambitious, but on the strength of the St. Paul’s /First Presbyterian trial balloons, we know we can pull it off. One of the lessons I learned watching Pere Bruno build St. Barthélémy from a dream and an empty lot is, stick with it even if you don’t have everything in hand.

Rob Fisher

Director, Partner for People and Place

“I feel we have a lot of people who want to do good things but don’t know where to get started. I think it’s the job of the Outreach committee to let people know what’s available,” said Crystal. “I’m not going to be the Chair next year, so I’m looking for some more people to help out.

“People see our budget come up on the Annual Report. But how are we spending the money? I think we ought to be held accountable by sharing that information. And I want to brag on the goodness of St. Paul’s.

“My grand vision is to see forty or fifty parishioners out there with “Work of Our Hands” on the back of their shirts. Just out there doing good things.”

Josh and Sara love St. Paul’s and are strongly committed to this parish. But why they love it, and how they came to feel that they were home at last, are two different tales.

Josh and Sara love St. Paul’s and are strongly committed to this parish. But why they love it, and how they came to feel that they were home at last, are two different tales. According to Wikipedia, “Kinison played on his former role as a Bible-preaching evangelist, taking satirical and sacrilegious shots at the

According to Wikipedia, “Kinison played on his former role as a Bible-preaching evangelist, taking satirical and sacrilegious shots at the  Joan: Grape-throwing might be hereditary!

Joan: Grape-throwing might be hereditary!

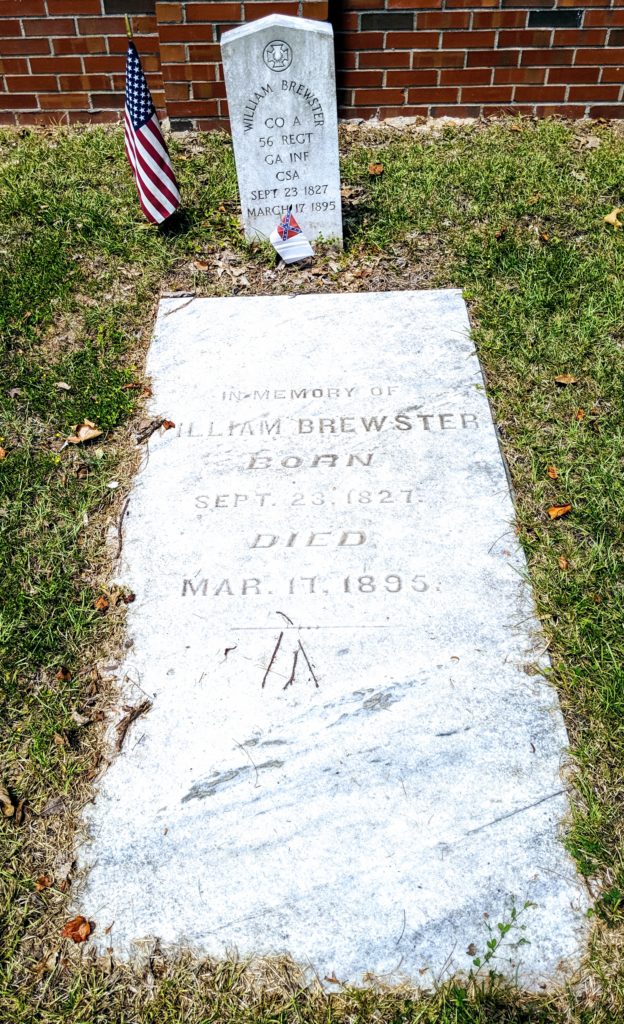

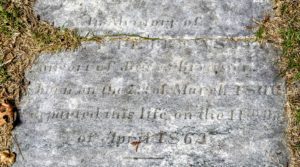

Behind St. Paul’s Memorial Garden wall is a small family cemetery. You won’t see it unless you walk around in back of the wall. This little burying ground once belonged to the Brewster family. It was located in the southwest corner of their dairy farm, which extended all the way from Roscoe Road to Highway 29. The family patriarch, James Brewster, was born in 1799 and died in 1893 at the age of ninety-four. Janett Brewster was born in 1806 and died 1862. Janett bore James thirteen children.*1

Behind St. Paul’s Memorial Garden wall is a small family cemetery. You won’t see it unless you walk around in back of the wall. This little burying ground once belonged to the Brewster family. It was located in the southwest corner of their dairy farm, which extended all the way from Roscoe Road to Highway 29. The family patriarch, James Brewster, was born in 1799 and died in 1893 at the age of ninety-four. Janett Brewster was born in 1806 and died 1862. Janett bore James thirteen children.*1

Another son is buried in the Oakland Cemetery. There is no indication of where the fourth of the Civil War soldiers is buried.

Another son is buried in the Oakland Cemetery. There is no indication of where the fourth of the Civil War soldiers is buried.

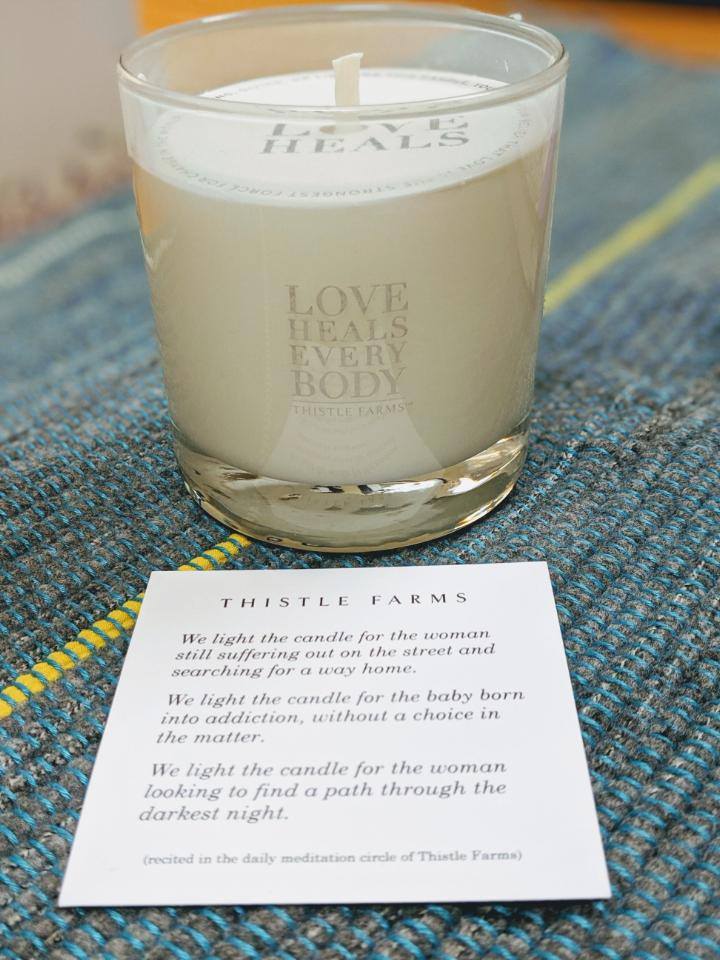

On May 19, a lovely Sunday afternoon, approximately 80 people gathered in the nave at St Paul’s Episcopal Church to hear from The Reverend Becca Stevens, author and founder of Thistle Farms, a social enterprise aimed to empower women who have been abused. She talked about a subject many of us would rather avoid; women who live on the streets. Her talk was anything but a downer, though; she focused on the help that her ministry offers to women willing to accept it.

On May 19, a lovely Sunday afternoon, approximately 80 people gathered in the nave at St Paul’s Episcopal Church to hear from The Reverend Becca Stevens, author and founder of Thistle Farms, a social enterprise aimed to empower women who have been abused. She talked about a subject many of us would rather avoid; women who live on the streets. Her talk was anything but a downer, though; she focused on the help that her ministry offers to women willing to accept it. After hearing from Ty, Becca herself, who is also a survivor, spoke. She was sexually abused from age five. She remarked on how hard it is to talk about an abusive sexual history. Even though abuse is not the fault of the victim, there is such sense of shame and self-loathing associated with being a victim that many bury it deep in their psyche leaving their personalities less than whole.

After hearing from Ty, Becca herself, who is also a survivor, spoke. She was sexually abused from age five. She remarked on how hard it is to talk about an abusive sexual history. Even though abuse is not the fault of the victim, there is such sense of shame and self-loathing associated with being a victim that many bury it deep in their psyche leaving their personalities less than whole. Becca told us of an especially difficult set of circumstances in 2017, at the height of the refugee crisis, where her group was able to turn things about. Desperate women were frequently stuck in refugee camps such as a notorious one in Greece. The men would leave to find new lives in Europe, but the women and children were often left behind. Without fathers, brothers or husbands as protectors, they were vulnerable to human trafficking. Philanthropic organizations find it extremely difficult to get into such camps to help, but with financial support from Wendy Schmidt (whose husband is the former Executive Chairman of Google) Becca’s group was able to organize five women who used their weaving skills to earn much-needed money for necessities not provided in the camp, such as dental work and fresh food. They wove welcome mats from the blankets and life jackets they had used on the crossing over the Mediterranean, where so many others had lost their lives. They sold the mats, trained other women, and were eventually reunited with their husbands.

Becca told us of an especially difficult set of circumstances in 2017, at the height of the refugee crisis, where her group was able to turn things about. Desperate women were frequently stuck in refugee camps such as a notorious one in Greece. The men would leave to find new lives in Europe, but the women and children were often left behind. Without fathers, brothers or husbands as protectors, they were vulnerable to human trafficking. Philanthropic organizations find it extremely difficult to get into such camps to help, but with financial support from Wendy Schmidt (whose husband is the former Executive Chairman of Google) Becca’s group was able to organize five women who used their weaving skills to earn much-needed money for necessities not provided in the camp, such as dental work and fresh food. They wove welcome mats from the blankets and life jackets they had used on the crossing over the Mediterranean, where so many others had lost their lives. They sold the mats, trained other women, and were eventually reunited with their husbands.